Behind the scenes with the Pixel Pulps.

Writer and game designer Nico Saraintaris tells me he is proud of Argentina’s literary heritage.

So, have I read Mariana Enriquez?

Are the translations good?

Where should I start?

I’ve read it once and I’m already itching to read it again.

It feels, I have to admit, exactly as I had imagined this conversation going.

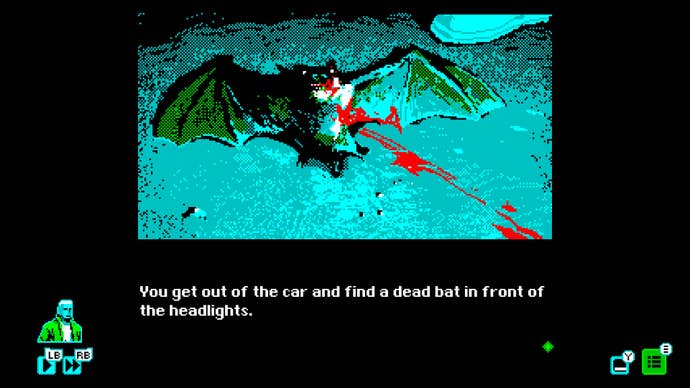

after being completely beguiled by their game, Mothmen 1966.

Pixel Pulp to its core, Mothmen isn’t just a videogame about the best of all cryptids.

It’s a game to go into knowing as little as possible.

The harmony of it!

It’s a game about a haunting, and it’s haunted me.

It’s a game about living with old soft-edged paperbacks, and it lived with me.

It’s heartfelt and so clever, so carefully made.

You use it for everything, even an in-game solitaire variant.

This game offers players a specific way of entering its world, and everything is channelled through that.

It’s a control scheme employed as a kind of air lock.

Okay, enough analogies.

So I got Mothmen a little bit wrong at first, even if I loved it.

And it’s one of the main motives I have for making games.

I want to bring some of that kind of thing back to videogames now.

That’s one of the reasons why I choose pixel art and that whole aesthetic.

I like the noise that you find in pixel art.

I mix a bit of comic books in with that.

I remember mostly things like the Spectrum, having cassettes and waiting for them to load.

He pauses, before refining his thought.

For me the eighties and late seventies were like this, an area where everything was exploding."

But a game like Mothmen strikes me as being a very pure and unforced form of immersion.

That dream you dream alone on a night with clear skies and a full moon.

So how to turn that into a question?

Then the pandemic came and everything fell apart.

Words and images are our main things that we think we can do stuff with.

The previous game was a really complex, really weird game.

It was maybe too much."

So the duo started thinking of something smaller they might make.

“Just the two of us,” says Saraintaris, picking up speed.

“We chose the interactive fiction genre, or visual novel.

Then we start to build on it.”

And all of this fed into what the game would become.

“The way we work is pure intuition,” Saraintaris explains.

“We decide on something and we keep pushing.

A pause to let that thought hold the air.

“This idea of fleeing forward!

“So that’s mainly our creative process - it’s messy, but it works for us.

“So in traditional development it sometimes takes one, two, three years.

To keep that kind of energy, we wanted to make the games fast.

It’s trusting each other a lot when we work.

I make all the pictures, Nico, he makes the puzzles, and writes.

The only feedback I get from Nico is when something isn’t working.

He’s like my guinea pig of sound when working.

If it doesn’t sound good, I know he’s going to tell me.

It has a flow, I think.

That’s what I like.”

I hadn’t realised how deep the pulp ethic goes, in other words.

It’s not just the subject matter, but the way the games are actually produced.

LCB are cranking on games.

The process filters into the work.

The pace and the know-how becomes a kind of watermark.

And that’s the thing.

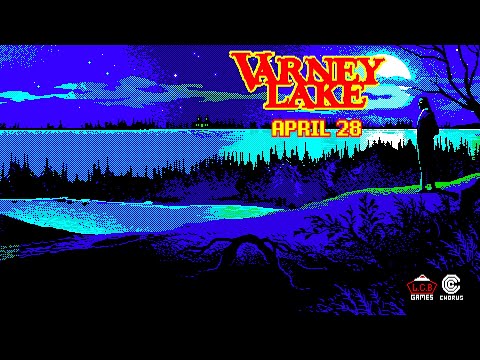

Another Pixel Pulp, with a few threads continued from Mothmen 1966, none of which should be spoiled.

I can’t wait to turn off the lights one night and properly play it.

And it comes from the same place, too.

“We like work ethic - like having a trade,” says Ruppel.

I like making things not as something precious but as…” A final pause.

How to put it?

“…As a discharge of creativity.”