He still remembers the maps they contained: his first atlas.

But there are two moments in Gaider’s life when a gift of maps leads to adventure.

In the second, he’s older, and already working at the job we know him best for.

He was a lead writer at BioWare.

One was to be science fiction and would becomeMass Effect.

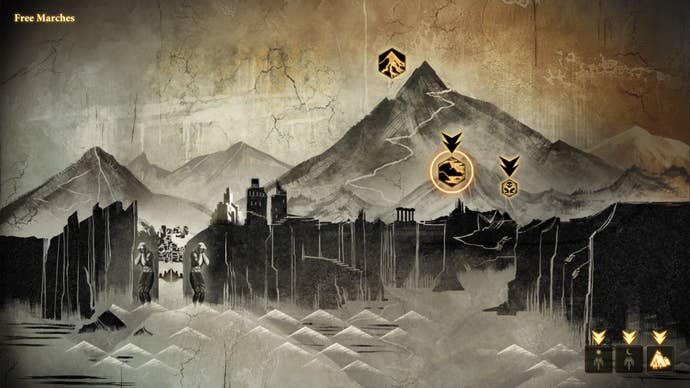

One was fantasy and would become Dragon Age.

Ideas had been swirling about what Dragon Age would be for a few months.

They knew they were going for Tolkien rather than Conan or Diablo.

But BioWare didn’t have a world, and that’s where the second collection of maps comes in.

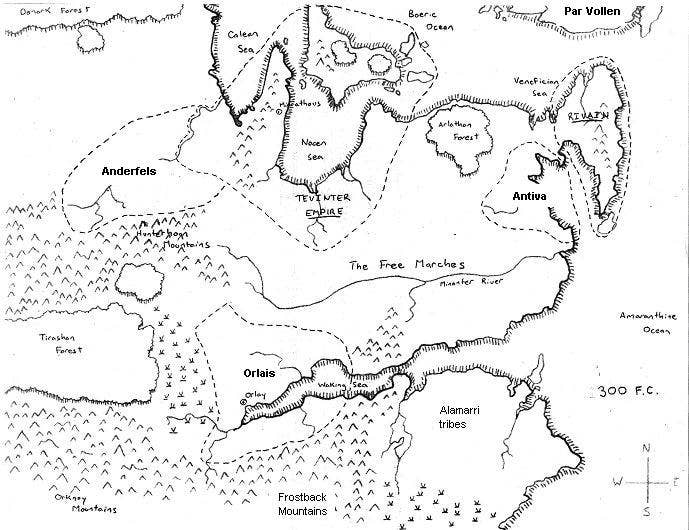

And almost immediately, he sketched a map.

I understand the impulse.

Maps have held power over me for as long as I can remember.

I can distinctly recall being fascinated by the large shapes of European countries I was colouring in at school.

Who lived in these elongated places in the north, and what were they like?

Maybe you know this map yourself.

Games that shaped me.

Places I spent a lot of time in.

There are maps I can still see when I close my eyes.

What is it about a map that gives it magical powers to bind us and pull us in?

And who better to ask than the curator of antiquarian mapping at the British Library, Tom Harper.

We haven’t always viewed maps or used them in the same way, apparently.

It’s more of a pilgrimage itinerary than a map.

All maps have a function, an agenda, a purpose.

Slowly, fantastical elements were elbowed out as the need for grids and precision came in.

That’s what he was taught.

But by those standards, some of the most famous maps I can think of wouldn’t exist.

- and the rivers are wrong.

Attitudes, though, have changed.

I’ve already written abouthow validating the Fantasy exhibition was for me.

Kirk was adamant from the beginning that they would.

“A hundred percent,” she tells me.

Again, just what is it about maps people latch onto?

“I feel like it’s a way of understanding the world,” Kirk says.

Maps are about people; places are about people.

“It’s a subconscious thing as well,” he adds.

“La la la, I’m going to call this Ferelden!”

Almost immediately, then, David Gaider sketched a map.

In fact, he corrects me, “I sketched a lot of maps.”

Tribes give way to kingdoms, and names we’re familiar with begin to appear.

Without it, he says a world will feel like a facade.

Before he sat down to draw, Gaider already knew some of the geographical elements he wanted.

Gaider also knew he wanted islands far up in the north, from which an unknown race could invade.

Because remember, the team didn’t yet know where the game they were making would be set.

And the trepidation is like, ‘I don’t know what I’m doing.’

“Whoisqualified to make a world?”

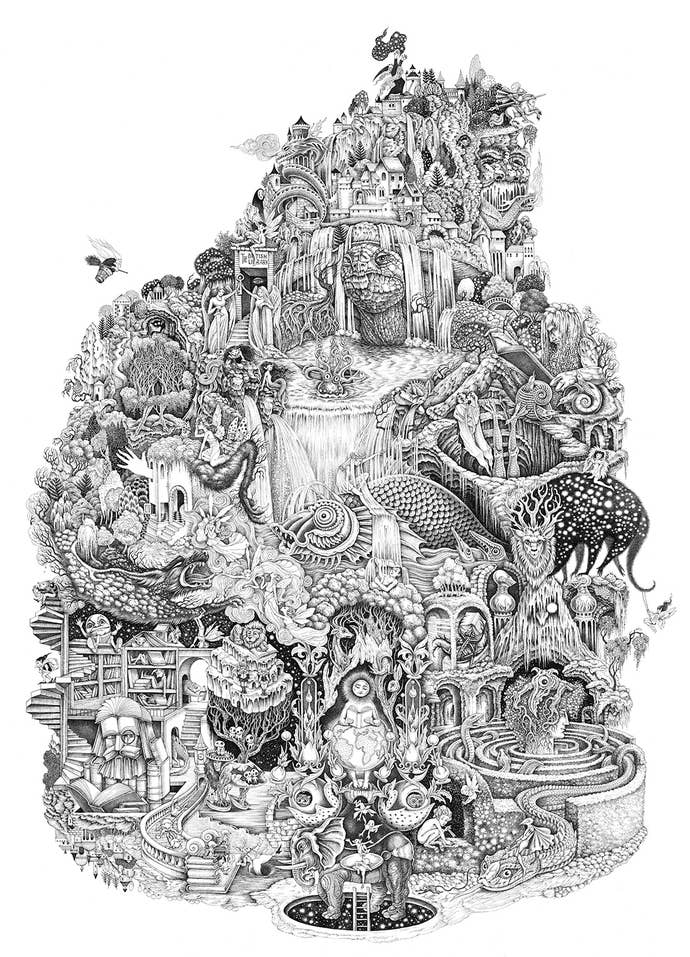

There’s a considerable overlap in all of these areas of fantasy, each supporting and fuelling the other.

If anyone knows how to create a world, they do.

It’s part of the hypnotic appeal of what he does.

King will follow the natural laws of geography to gradually pull a world into existence.

It’s a process that helps lessen the overwhelming feeling a blank page can create.

But before any of this, another crucial step comes first: communication with a client.

Discussion, understanding, immersion in whatever world that’s to be made.

Baerald’s one of the most decorated map-makers I speak to.

She’s worked in tabletop RPG land, she’s worked on fantasy books.

Like King, Baerald creates almost exclusively physically, painting her worlds onto paper using watercolour.

“I believe a perfect map should inspire players and readers from the first glance,” she says.

Open any D&D book and you’ll see his work.

Unlike Baerald, Schley works digitally, in PhotoShop with a Wacom tablet.

But he too draws large to small, eventually getting to the minute details he likes most.

But to do so, a map also needs space, Schley says.

Space for us to pour our imaginations into.

“Leaving that room to breathe is absolutely essential,” he tells me.

He wants your mind to consciously, or subconsciously, imprint itself upon what it sees.

“Oh,” he said awkwardly when they were presented to him.

“I didn’t want it to look like this, exactly.”

“And I’m like, ‘You know what?

You got a point,'” Gaider says.

This is mostly anger at himself, though, for not doing more about it.

“But to where?”

But it speaks to something he’s noticed in his decades working in games about artists and writers.

“They really speak two different languages,” he tells me.

They process things differently and they tend to care about different things.

They wanted clear visual cues, not piles of backstory.

I think we would have played our cards a little closer to our chest."

It seemed like a good idea at the time.

It wasn’t particularly memorable, but it looked nice.

The game didn’t go down well.

“Its highs were really high, and its lows were really low,” Gaider says now.

“It was very unpolished.

More importantly, it meant everything would need to change again for Dragon Age 3.

We couldn’t ignore them then, or take them for granted.

We had to use them to navigate, so we were constantly reminded of them.

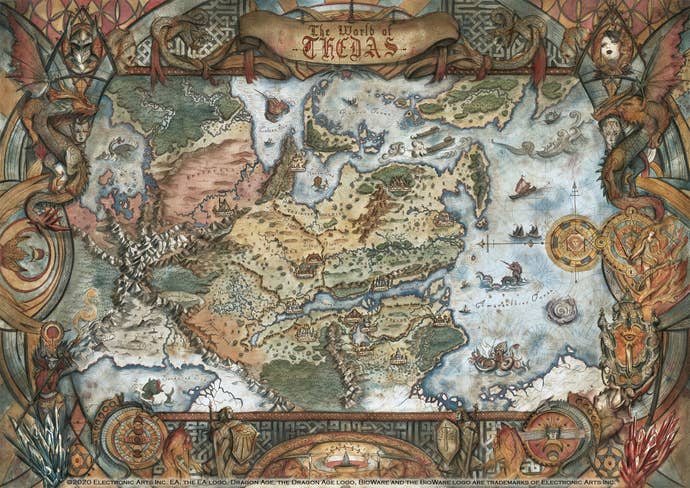

Today, they’re kept alive as collectible extras for Collector’s Editions.

But not all games follow today’s norms.

Shouldice also tries to make you puzzle over the map in Tunic.

Others are more blunt and call it, simply, theft.

“There’s no voice there,” says Mike Schley.

It’s hollow, soulless.

“It lies to you at least a couple times,” Shouldice says.

It’s smaller than the actual world, he says, and missing one zone entirely at the beginning.

It’s also missing information and it has overlapping scenery, which obscures details underneath.

“So you get this exciting, revelatory moment where you’re like, ‘Oh a map!

I’ll just use that to figure out where I’m going,'” he says.

“And you realise it’s maybe an unreliable narrator or it has incomplete information.

But the sense of scale was an illusion.

People were now joining the team who were already fans of the series.

This was no longer an imaginary world; Thedas felt real.

And perhaps it no longer needed Gaider to steer it.

Really, he’d had enough of wizards and demons, and Anthem wasn’t the tonic he sought.

That game, incidentally, only featured a small map for travelling between city locations.

It’s an anxious wait, as you’ve got the option to imagine.

I’m not sure how I will feel when Dragon Age 4 comes out.

What if they bring back some characters that I wrote?

They’re going to Tevinter so what if Dorian’s there?

But it’s no longer Gaider’s map, and no longer Gaider’s world.

It’s all of ours.

What have I learned from all that I’ve heard?

For Gaider, maps are snapshots of history, photocopied slideshows explaining how places came to be.

It goes onwards, outwards.

For Tom Harper, maps are more like self-portraits, reflecting our lives and experiences back at us.

Maps are different things to different people.

That didn’t initially seem like the answer I hoped for when I set out.

And yet, looked at from a different way, I think maybe it is.

Perspectives: that’s what I’m hearing about here.

That’s what I’m hearing about from everyone.

It’s all something to do with the way maps show us different perspectives on different worlds.

Maybe this is what maps do.

Yet suddenly we could see beyond the horizon, beyond mountains, beyond seas.

Our tiny viewpoint was replaced with something panoramic.

And we could all do with a bit more wonder.

A huge thank you to all the people who spoke to me for this piece.

hey take a look at their wonderful work!