Both products wear their engagement on their sleeves.

Both present themselves as informing the player about the real world, about real events and real places.

They seek actively to change minds.

To educate, to inform, and to influence for the better.

They appeal to cosmopolitan virtues of solidarity and global citizenship.

Consume us, they promise, and you could better understand Syria.

Consume us, and make the world a better place.

Whether this promise is credible or not, both experiences do share an aspiration to informing global consciousness.

Both also share a marked absence.

They are hauntingly empty of plausibly human beings.

Age-old edifices are left to speak, however eloquently, for themselves.

Syrian Warfare, meanwhile, ventriloquises its miniscule combatants only to issue polemical pretexts for gameplay violence.

Wicked White Helmets gleefully fake atrocities, colluding with lying Western journalists to smear the noble state.

The protagonist dismisses his family in the prologue with a curt’Quiet, woman!

Do as I say!

‘,and they are never heard from again.

‘What kind of Arab would I be if I didn’t have a RPG buried in my yard!

‘remarks another of its crudely racialised caricatures.

What kind, indeed.

Yet here too, games struggle with the task of communicating the subject to the audience.

Games distinguish themselves from other media not least in their concern for agency.

This surely makes it a better game.

Real life is choked by exorbitant paywalls and littered with interminably and inexplicably un-skippable cut-scenes.

Eurogamer would not Recommend a trek for asylum across Anatolia.

It betokens a deeper chasm between medium and message.

“Real life is choked by exorbitant paywalls and littered with interminably and inexplicably un-skippable cut-scenes.

It does not always respect our agency or value our time.”

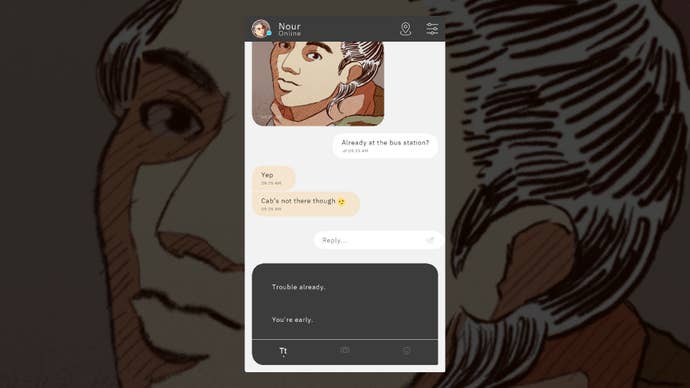

Would that best help us to understand the real Nours, the real Majds?

It is far from clear that it would.

This is not only true because suffering freely chosen is not the same as suffering imposed upon one.

It is rather because those who suffer tragedy are so muchmorethan their suffering.

It is precisely thatmorewhich makes their suffering tragic.

This is not a form of denial.

Real solidarity calls us to know the dreams of the other, and not just their nightmares.

This is something developers can perhaps learn from Mahmoud Darwish, the poet with whose verse we began.

His poetry crosses boundaries of geography, religion, and politics precisely through its acutely personal lyricism.

But it is not itself his spirit.

The poet shares his living humanity, and we understand his exile only through it.

He does not first describe his exile and then attempt to humanise it.

His focus on the lived, the lyrical, the painfully beautiful is not denial but affirmation.