How Larian honoured BioWare’s story while creating its “most heroic” playthrough yet.

Bookmark this for later.

Being evil in games excites me.

I cannot resist the temptation of pressing a big red button.

I’ve pushed every red button I’ve found and the results have been extraordinary.

It’s not common.

Being a villain in a game is anathema to being a hero.

How can you be one and also the other?

It could mean the death of companions and majorly upended story events.

Was I ready to cede so much control to something in a role-playing game?

I’ve meddled with gods and become a literal, rampaging monster.

The game has welcomed me.

I have revelled in it.

The Dark Urge might have been revealed late in development, yet it’s anything but an afterthought.

But the story of the Dark Urge began a long before Baldur’s Gate 3, I discover.

It began long ago with BioWare’s original pair ofBaldur’s Gategames from the late 90s.

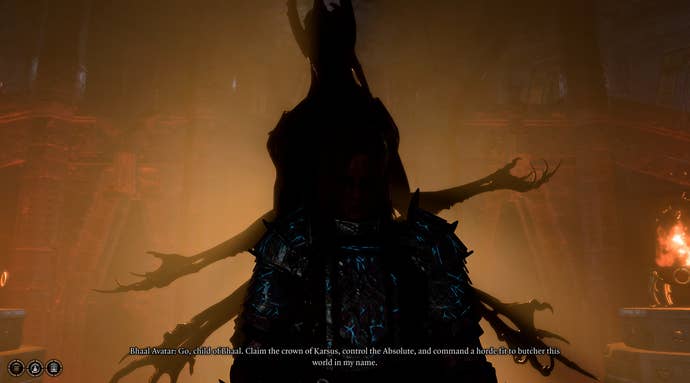

There, the story of the Bhaalspawn was told.

And he did it because you were his child, a Bhaalspawn.

Baldur’s Gate 2 continued the story but at higher levels with higher stakes.

Again: sound familiar?

The story of the Bhaalspawn tied those old games together.

It was a fake-out.

“It was like the ace up our sleeves that we will have this thing.”

“It was always going to happen.”

The problem was: how?

But a lot of those early ideas were falling on infertile ground.

“We went through god I don’t know how many versions of it,” Smith says.

Did they wipe each other out?

Where were they now if they didn’t?

And how would a new character in Baldur’s Gate 3 be related to them?

Larian also wasn’t sure what role the Bhaalspawn character would play.

Would it be the player character or a companion?

But because you weren’t in their head, seeing their struggle, it wasn’t very captivating.

“It’s probably more interesting if I play as it,” Smith and the team thought.

Smith took an early swing at the Bhaalspawn idea that could have drastically changed the game.

They come up to you and say, ‘I’m in control now.’

And it’s Bhaal.

He just steps in and he says, ‘Fuck them - that’s finished.

You listen to me.’

“We had this thing where he literally forced the tadpole out of you,” he says.

“He was like, ‘No, no, no.

I’m the one who’s in charge around here.’

Well, he pushed it to one side and it had no influence on you any more.

So then it became this inner struggle between Bhaalanda tadpoleandyour own personality.

It was too much.

Nothing the studio tried worked well across the entire game.

It needed something else.

It needed Baudelaire Welch.

“Almost like you’ve become this deranged leftover.”

And suddenly, everything clicked.

They barely needed to be explained.

“Beau managed to crystallise it in a way where it feels human,” Smith adds.

Intrusive thoughts: people get it.

There was a problem: Welch wasn’t like their mother in one crucial regard.

“I’m so squeamish,” Welch blurts, laughing.

“I hate gore!”

How on earth would they write the depraved thoughts of a murderer?

Yet it was precisely this squeamish nature that Smith believes made them the ideal candidate for the job.

“That came from somebody who’s like, ‘This stuff is fucking horrible!’

Fucking rivers of blood man - cool!'”

Welch’s way of dealing with it was deliberately not to write gory scenes.

Instead, they had the Dark Urge imagine things in a more abstract way.

Consider the scene in the Druid Grove where you’re dealing with an injured bird, for instance.

“The average player sees it and helps heal it,” Welch says.

Welch also came up with another crucially important vessel for telling the Dark Urge’s story: the butler.

He wears a top-hat and tails and radiates malice, though in a ridiculous, pantomime kind of way.

And he’s full of encouragement for your dastardly deeds.

It’s an idea inspired by Anthony Burgess' A Clockwork Orange novel.

Sceleritas Fel, as the butler is known, didn’t exist in the earlier Baldur’s Gate games.

It was a character Welch had a great deal of fun writing.

“I have something wonderful for you, dear mouldering Master,” he announces, snivelling with malice.

“A part of your past is here for you.

Try on your new jimjams!

They’re a present from Father, it would be rude not to.”

I remember in that moment wondering what Fel meant.

Did he really mean pyjamas?

“I was amazed it didn’t get cut,” Welch says, referring to the jimjams line.

I’m glad that you remember that line!”

“I said I was squeamish at the start,” Welch says.

“It desensitised me to everything.”

It can’t all be humour though.

For the Dark Urge to work - for evil to work - it has to have consequences.

One such moment happens early in the game when a tiefling bard called Alfira joins your camp.

They ask if they can stay the night; it’s a big mistake.

It’s a sharp reminder of what you could do.

It’s show, don’t tell.

you better experience having done this at least once."

In other words, the Dark Urge needed moments for you to reflect.

Being evil shouldn’t be easy.

I felt similarly despicable when I destroyed the refuge of Last Light in Act 2.

“We did try and make it hard, emotionally,” Smith says.

There were also moments where I felt the game was interrogating my motivations.

I was taken aback.

through characters," Smith says.

The drow commander Minthara, the baddie in Act 1 but who can become a companion, exemplifies this.

It’s a lonelier road, too, the evil one.

“We probably should have given a little more,” he says.

There are always going to be ways people approach the game Larian couldn’t predict.

What surprised Welch was how many people played the Dark Urge and tried to resist it, and Bhaal.

“I was always writing with ‘evil evil evil evil’ in my brain.”

But Smith, like many players, loved it.

Usually the gods treat you like toys, which is a running theme in the game.

I don’t think this is fair.

You’re a hero.

You don’t deserve this shit."

“People get a lot of reward out of being a good person.

I’ll admit, I thought of it in the same way.

Somebody’s probably going to want to because it’s roleplay.'

That leads you to having to cater for very, very broad choices.”

Similarly, Will can behead Karlach for motivations entirely his own.

Evil does not depend on being Bhaalspawn.

Baldur’s Gate 3, though, does, as I well know.

Realising that takes a lot of work.

There are some things Welch would have liked to have done differently with the Dark Urge experience.

Simply, they would have liked to have more Dark Urge moments throughout the game.

The in-development Patch 7 will bring much-needed, expanded evil endings to the game.

As it is, it ends rather abruptly, but these should extend it greatly.

Smith is really excited about what the team has done.

Welch has a long history with fanfiction, and has seen people shipping the two characters.

They’re slightly ashamed they didn’t see it sooner.

I certainly ripped Orin apart easily enough in our duel.

Outside of that, Smith is pleased with everything the studio has achieved.

“Which doesn’t mean that I think we did it perfectly,” he adds.

That’s how delicate it is."

Despite preconceptions, the Dark Urge is no mere second playthrough afterthought.

It’s the perfect encapsulation of how deeply Larian values choice and consequence.

It is, perhaps, the best of Baldur’s Gate 3.

You just have to have the nerve to play it.