Yet there’s a lot to love, I think.

This is a rarity in the world we’re about to enter.

Pens and paper and layers of narrative, some of which cannot be trusted.

Pentiment is a narrative adventure game set in the sixteenth century.

But let’s linger just a little longer on the act of writing.

Because, really, the pleasures and the politics of text and of books are everywhere here.

This room and rooms like it were once key to the church’s power.

They owned the books and they made the books.

And they could make books disappear.

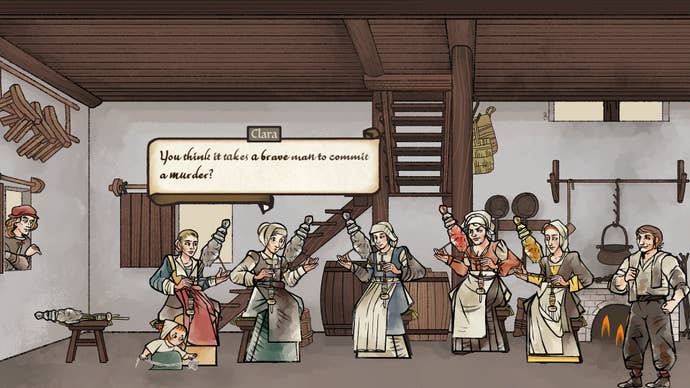

And most importantly when it comes to text there’s speech itself.

More: when they shout, the text grows agitated and shakes.

When they are shocked, ink is splattered across the page.

Text divides as well as unites here.

Pentiment keeps you busy early on while all this clever stuff soaks in.

Maler is no monk, we learn.

Maler must clear his friend’s name by finding the real killer.

And so the game falls into a rhythm.

All very Name of the Rose.

Then the moment came when I had to explain my thinking.

I checked my watch: five hours or so.

And then I got a big surprise.

This wasn’t the end of the game, but rather the end of the first act.

Then it leaps forward in time and becomes something stranger and richer.

Maler returns to Tassing older and - perhaps - wiser, a successful artist with his own apprentice.

Where can the game possibly go from here?

Isn’t everything solved and sorted away?

It isn’t, of course, and the game blossoms.

It’s interested in the impact of crimes and their punishments on a small community.

In fact, make this two things I didn’t understand.

The Name of the Rose takes place in 1327, deep in the medieval world.

Pentiment, meanwhile, begins in 1518.

In 1518, Leonardo had only a year to live, while Durer had already completed his Melencolia.

- but for some people in society things were actually changing pretty fast.

Look deeper and you see this last point particularly clearly in Pentiment.

In the town of Tassing there are already printers working, allowing ideas to travel faster and further.

Who gets to write it down, and what lies beneath those words?

And what is the cost?

This might be the game’s masterstroke.

Not really - and maybe I just need to think about the ending some more anyway.

There’s an awful lot to think about in Pentiment, after all.

And this is the trick, isn’t it?

The same trick that The Name of the Rose plays.

Eco’s novel is dense and complex and theoretically slightly off-putting.

A book that has footnotes in Latinwhich it doesn’t bother to translate?

Pentiment works the same magic.