I get locked out of my house quite a lot.

By “I get locked out,” I mean that I contrive to accidentally lock myself out.

Which is absolutely enough, thanks.

(Maybe five times a year.)

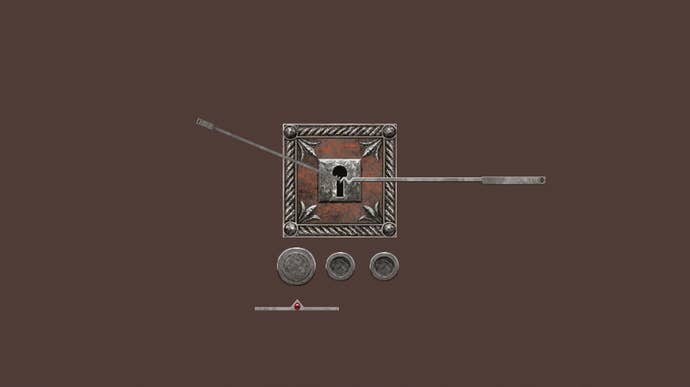

The Museum of Mechanics: Lockpicking

Hero!

The locksmith’s name was Matt, and I am so happy I met him.

Maybe six times a year?

Bump keys and McDonalds robbers!

It was the perfect moment for me to be talking to a locksmith.

And I really lucked in with Matt.

He is a locksmith, but he’s also genuinely fascinated by locks.

It has been a pretty good few years for fans of lock-picking and that sort of thing in games.

By which I mean two games have come out.

The first wasSophie’s Safecracking Simulator, by the brilliant Sophie Houlden.

An absolute treat, asBertiediscovered.

Turn the tumblers and learn about this arcane world!

The second is The Museum of Mechanics: Lockpicking, by Dim Bulb Games.

It’s a glorious, scrappy thing, more cabinet of curiosities than museum, I think.

There is a special affinity between locks and games, I think.

And a world of moving pieces turning and sliding and slotting together just out of sight.

The instance of the fingerpost.

The moment the key fits.

The moment the whole thingclicks.

It is a chilly morning in Newhaven.

“Put this to your ear,” says Matt, handing me a lock.

Precision does wonderful things to language.

Mechanical watches give us words like “escapement” and “complication”.

They have “crowns” and “movements”.

Locks give us “strikes” and “keeps”, both serving time as nouns.

Locks are clearly tricksy things.

Matt pulls out a little penknife-alike and unfolds one of its scribbled prongs.

He places it in the lock and I listen as he moves the pick back and forth.

A pause while the lock builds itself in his mind.

I close my eyes.

I did hear that.

Not quite a click.

This was a click’s quieter nephew.

But a joy all the same.

“That’s two pins,” says Matt.

“One or two.”

Words are everywhere in locks, curious and surprising.

And in Matt’s locksmith shop in Newhaven, things are everywhere too.

Curious and surprising things.

Brass with its dozy spreading stains.

Little boxes of bits and pieces, filed on shelves.

But also buckets of stuff laid out below tables.

Vices and clamps and objects with motors.

Trays of tiny items called “shims”.

Walls of peculiar wrenches and increasingly delicate tools.

Locksmiths are perhaps the dentists of the urban world.

He was totally up for it.

We set up a computer in the back of his shop.

I think it’s Sherlock anyway.

It’s abstract, and joylessly so.

Lockpicking rendered as the annual financials for a motorway service station.

And would Holmes really have to pick a lock anyway?

Does he do that in the stories?

(Genuinely asking.)

Is this close to what happens inside a door, though?

As an answer, he tells me about the shear line.

“So the pins inside a cylinder lock are different heights,” he tells me.

He drops them into my open hand, cold jiggling weight in my palm.

“Pins and springs,” says Matt.

“I’ll show you the bits and bobs.”

“These here are just normal pins,” he says.

“Just cylindrical, two-point-nine millimeter, great.

And you could have these pins arranged at the top or the bottom.

He shakes a handful with obvious delight.

“These are three millimeter, three-point-one.

They have serrations, grooves.

He continues for a few minutes, but from here, I promise you, the ground drops away.

Many locks build on these basic ideas incomplicatedways.

And yet you put them together in new arrangements and you get, what?

You get something it’s possible for you to work away at for hours.

But not Sherlock Holmes' lock-picking game.

Padlocks are trickier to pick than locks, Matt tells me.

Slightly wistful, I think: he tends not to pick them anymore.

I load up another lockpicking minigame.

This is a personal favourite.

You’re inside the lock, as it were, viewing the cylinder from the side.

You move the pick along each pin, bouncing it to find the direction in which it clicks.

Whenever I play Splinter Cell I look forward to these little moments.

“This is an individual pick,” Matt says, moving around the screen.

“So this pick would pick pins.

you’re able to feel when you’ve got it right and it clicks.”

So you just keep resetting, resetting, resetting and it buzzes away - zzzzzzz!”

“Yes and no,” he says.

“More often than not the battery goes flat so it doesn’t get used that much.”

Matt likes Splinter Cell’s minigame, but he’s being polite I think.

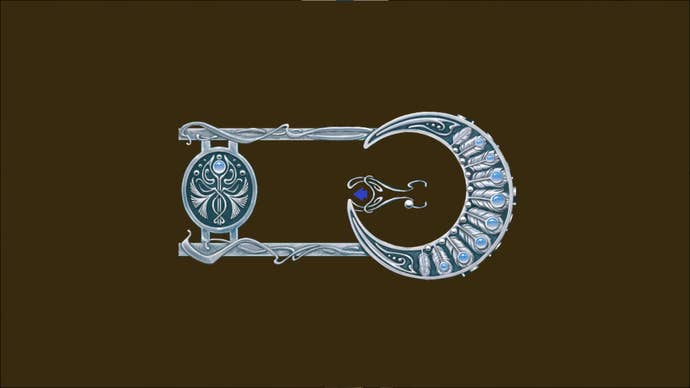

We play through a few more minigames before landing on Skyrim, which I already know is his favourite.

We are outside the lock here.

We have a pick and a tension bar.

An ornate piece of ironwork around the keyhole, too: someone’s doing alright.

“Applying tension hopefully holds things in place,” Matt says.

“I love the Skyrim one.

I thought this should be an unlock-your-phone sort of thing.”

He leans forward and moves the tension bar on the screen.

He moves the pick.

“It’s there,” he says.

“I can feel it but I can’t get it.”

Some part of his mind is inside this imaginary lock.

After a second or two, he pushes his chair back.

I ask him if he thinks games do a good job with locks, by and large.

“Terrible,” he says.

And then he nods at the screen: “Well, Skyrim was really good.

And you have a certain number of picks.

That’s quite good.”

Does that feel real then?

He nods and goes back to the lock on the screen.

He moves the tension bar.

“So it’s over here.

A sort of poetry of wordlessness: no easy sentences for what’s going onin there.

I’ve thought about this noise a lot, and I’ve decided it’s basically a garbledcrunch.

It suggests to me that there are a lot of little pleasures in locksmithing.

On this topic: during a lull in the Museum, I ask Matt how he got into locksmithing.

Then, one day he came across lockpicking and it just seemed interesting.

He looked it up.

“And it showed you what sort of shaped tools you need.

So I’ve got some Allen keys, and I’ve bent them and had them smoothed.

And I picked some locks.”

He thinks back and frowns.

“The first one took about seven hours.

And then, like, seven minutes and then 20 seconds.

Once you learn the signature?

Not a problem.”

It sounds like it was a hobby at this point.

But one day he turned up at a friend’s motorbike shop.

“He had three big padlocks.

And I spent about 20 minutes and I picked them all.

I thought: go on.

That was easy.”

An idea settled in his mind.

And maybe its time had come, you know?

Maybe Matt was looking for something new.

For a while he’d had a garage himself.

Interesting work if you have an intricate mind that’s attracted to intricate things.

He nods to himself.

“So I became a gas man after doing security stuff in between.

200 boilers, 200 components, a lot easier.

LPG and you know the bottled gas they use on caravans?”

Those caravans, though.

It’s not fun, not fun.”

50 locks, 20 components and it’s warm.”

He makes it sound like a practical choice, and I’m sure there was some of that.

But there’s more here surely: a kind of harmony.

“Yeah,” he says, smiling.

He pauses to think.

“But yes, the whole lockpicking bit is a mechanical puzzle that’s minute and intricate.

And some of them have extra bits on the side.

Some of them have pins within pins, there’s all manner of different things.

Some of them have magnets to try and make a little bit harder for people to pick.”

And then it clicks, as you might put it.

This has been something of a trend when it comes to my chats with Matt.

Those pick sets you’ve got the option to buy online, with dozens of different tools?

But that’s locksmiths anyway.

Real burglars heft a lawnmower through the window, remember?

All of this raises questions.

Primarily: if burglars are ignoring locks, why are locks still getting more complicated?

“Because it’s an industry thing,” Matt says.

So we’ve got locks that are British standard three-star locks?

Wait, how are people going to die?

“People will die because of fire regs,” says Matt.

But if a key is left on the outside?

The thumb turn won’t work with the key on the outside.

You’d have to run outside and open it again.

But you’ve got the option to’t if you’re in a flat."

“They make them harder and harder.

And burglars aren’t picking the locks, right?

The only people that have to get through them are locksmiths.

So we just go through more and more drill bits.

We buy them in bulk.

It’s just so much easier to drill it than pick it.

Everything’s just been designed to drill it out and put a new one in.”

So if not even locksmiths are picking locks as much as they used to, is anybody picking locks?

And this brings us back to the Museum, and back to games.

Curious people all over the world are picking locks.

Let’s take another look at that definition Matt offered.

It was lovely.Lockpicking: a mechanical puzzle that’s minute and intricate.Turns out some people really adore that.

It gives them something they need it their lives.

Around the world - Manaugh talks about it brilliantly in Burglar’s Guide - there’s this newish sport.

It’s called locksport.

People picking locks for fun.

People cracking safes for fun.

For the puzzle of it.

The intricacy of it.

The moment where things click.

The instance of the fingerpost.

Over the last few years, Matt and his colleagues have been serving this growing community.

“Well, it was never done as a moneymaker,” Matt says.

It started with the team’s charity collection: Heart of Brass.

Here’s Tess, Matt’s daughter and apprentice: “We collect people’s scrap keys and stuff.

And we donate it.

We cash it in and then we donate the money to local charities.

So we snapped them in half and put them on eBay.

And that was the moment that we realised that no one was marketing a product for these locksport people.

“Well, one Saturday afternoon I’ve put about 100 cylinders on the table,” says Matt.

“Photographed and then put them on eBay in lots of 20.

And within two hours, it had all sold.

It was ridiculous.”

I ask Tess if she is into locksport herself.

She thinks about it for a few seconds.

“I enjoy working with locks,” she tells me.

“You do!”

“It’s a quirky trade,” says Tess.

“There’s nothing else quite like it.

It teaches you a lot.

But I can never look at my front door the same.

I don’t trust it anymore.”

This is where they’ve sent locksport materials around the world.

“We send out bits and bobs,” says Matt, reverting to his favourite phrase.

“We send some sample kits of things.

We send some basic packs that includes locks for people to pick.

We produce kits for people to be able to pull a lock apart and make it harder to pick.

This is enthusiast stuff - nobody’s using this on their house.”

“We’ve got someone in Colombia, they buy about 140 pounds' worth a year.

This little sport has taken us to St Helena!

There’s almost nothing there!

Reunion in the Indian Ocean!

China not so much.

When you send stuff to China it never arrives.”

“It’s a quirky trade.

There’s nothing else quite like it.

It teaches you a lot.

But I can never look at my front door the same.

I don’t trust it anymore.”

He traces a finger over some of the map, some of the pins.

“Not much to India, not much.

America is a huge market.

You’ve got the Youtube guys.”

He mentions names: Bosnian Bill and the LockPickingLawyer are amongst the big players.

Bosnian Bill has featured Matt’s kits a bit on his channel.

So we spend a few minutes watching Bosnian Bill on Youtube.

And they’ve done wonderful things.

In Jenny LeClue, you pick locks using a child’s hairpin with a bright butterfly on the end.

InSleeping Dogsit’s all clean and abstracted, just line up the pins.

It’s incredible how many memories of the wider games return with these little snapshots.

Another Museum of Mechanics right there.

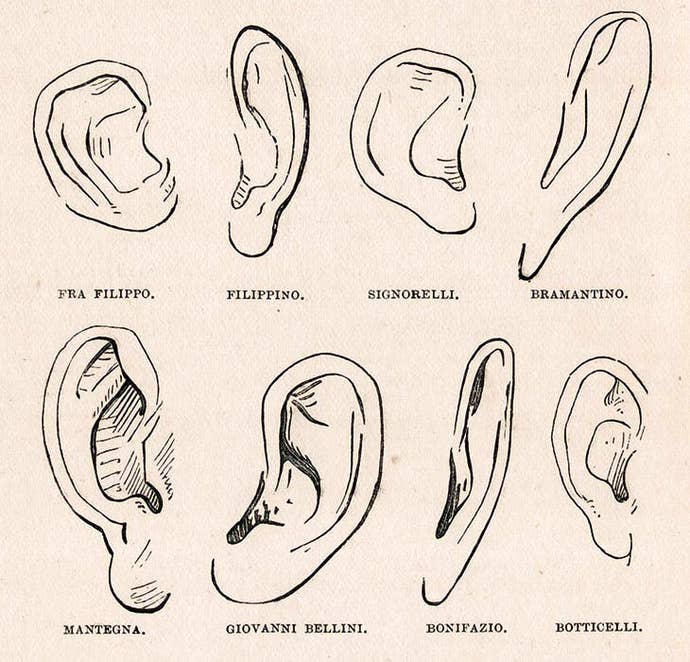

I love Dim Bulb’s Morellian approach.

The kind of thing digital games will always have to approach with at least a degree of abstraction.

And that abstraction is where the craft comes in.

Put this to your ear.Locks are brilliant, aren’t they?

Paranoia and security fears, yes.

But also ingenuity written in brass and steel and plastic.

Consider it now, for one last moment: Lockworld.

That is, consider the world within the lock.

A continent formed of ingenuity and graft.

And then the whole landscape starts to turn.

Any inevitable mistakes in the piece are mine and only mine.