“Ask and it shall be given you; seek and ye shall find.”

Clayton Hutton’s letter was a challenge.

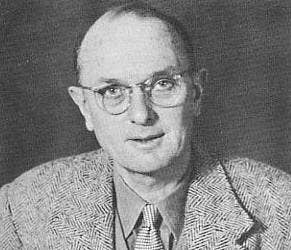

Houdini received this sort of letter every day, but Clayton Hutton’s was different.Clayton Huttonwas different.

And Houdini did accept the challenge - but with one condition.

He would visit the lumber yard before the show to meet the carpenter charged with the case’s construction.

This was the beginning rather than the end of his wiliness, however.

The crate was flawed, Houdini emerged victorious, and Clayton Hutton lost out on 100.

All the same, he had learned a lesson that would prove far more valuable to him over time.

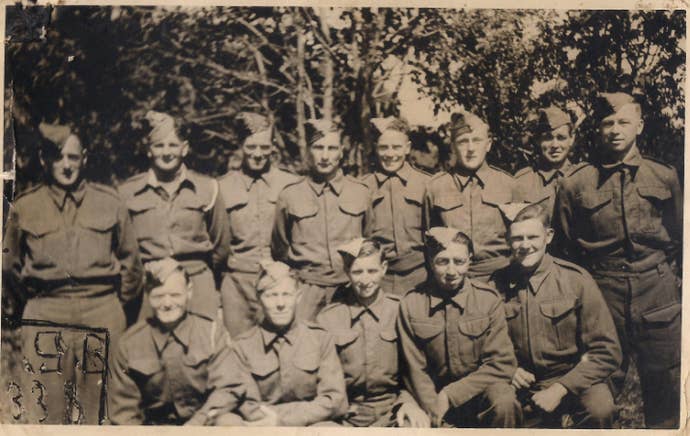

The 51st

My maternal grandfather met this ally in a fortress in Poland several decades later.

His military service proved brief and bewildering.

My grandfather never fired a shot.

He always told us his war had lasted an hour and five years.

St Valery was the hour.

The five years were to come.

With its familiar streets, its familiar rituals.

“Clayton Hutton was the ‘joker in the pack’.

Where would he have gotten them from?

Nobody had ever thought of using POWs as anassetbefore.”

That set gave my grandfather his war stories.

As for my grandfather?

A transatlantic birth

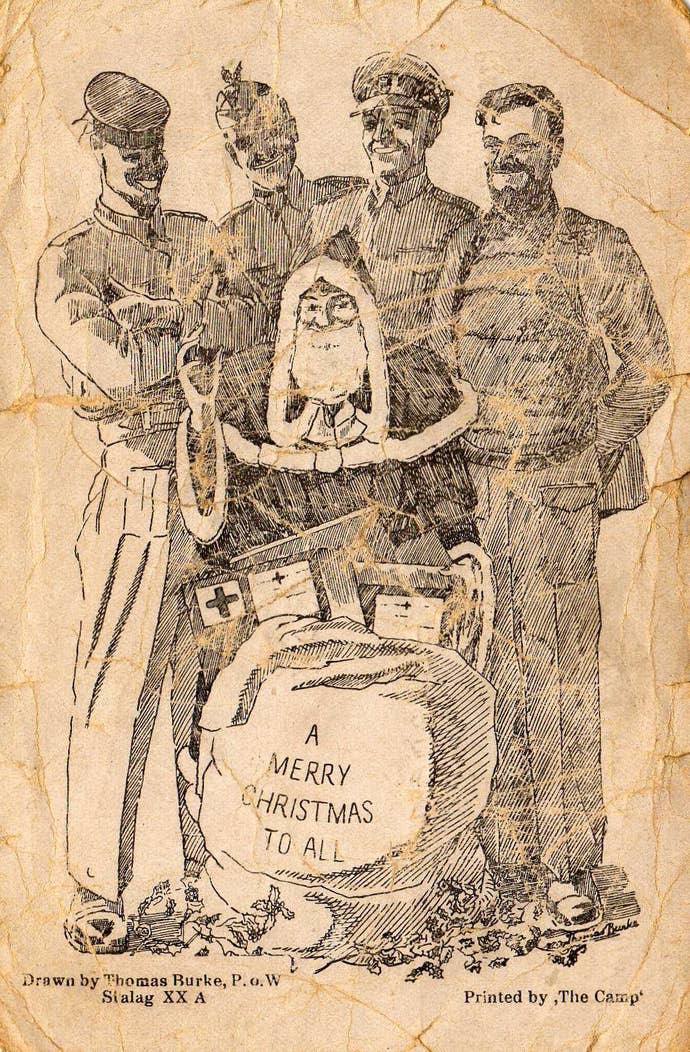

Cinematic acts of heroism were thin on the ground at Stalag XXB.

Nobody dug a tunnel as far as I can tell.

Nobody hopped over fences on a stolen motorbike.

A victory with the cheapest cards in the deck!

I was fiercely disappointed.

“That’s virtually impossible!”

Phil Orbanes almost yells at me when I tell him the story over Skype.

Orbanes was destined to love Monopoly.

“Boy, it was an eerie sight.

I wait, but there’s nothing more.

Through the cold crackle of Skype I can almost hear him shiver.

You had to make your own fun back then.

A transatlantic phone call lasting three minutes and costing $75 saw Monopoly landing in England a year later.

It even overcame a brief Fascist backlash in Italy.

“By the late 1930s, by the start of the war, Monopoly washuge,” Orbanes explains.

That made the game.

Despite service as a pilot during the First World War, Clayton Hutton was not a career military man.

Theatricality and general trickery ruled.

The best book I’ve read on the outfit - MI9: Escape and Evasion, by M.R.D.

MI9’s world was frequently a thrifty wonderland of the improbable and the hand-made.

Where would he have gotten them from?

Nobody had ever thought of using POWs as anassetbefore.

“This present war is to be conducted across vastly different lines.

This sounds insane, of course.

This was a typical example of his thinking.

Even his nickname - Clutty - sounds like it’s being compressed by g-forces.

He never used the phone either, for fear of wiretaps.

And yet - and yet!

He got results quickly, too.

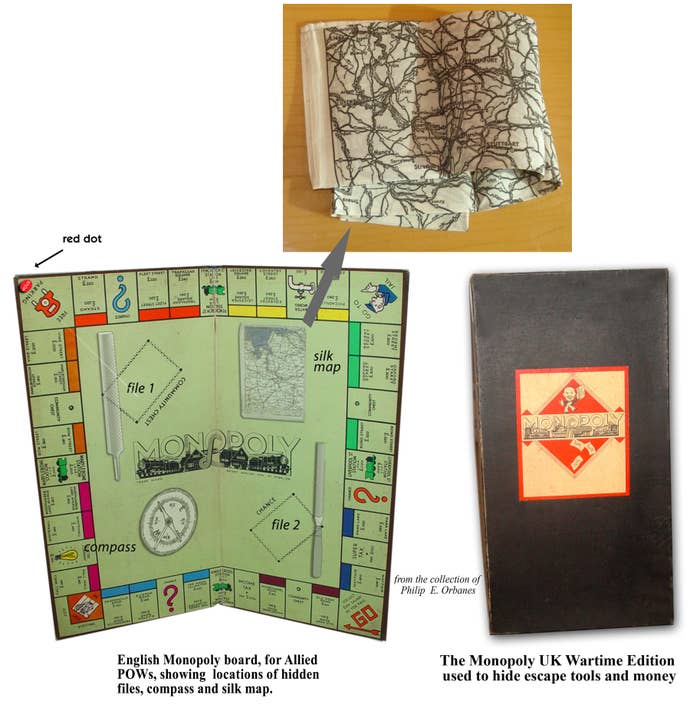

This was a fold-out contraption that housed lock breakers, screwdrivers, and wire cutters.

He saw inspiration for escape aids everywhere.

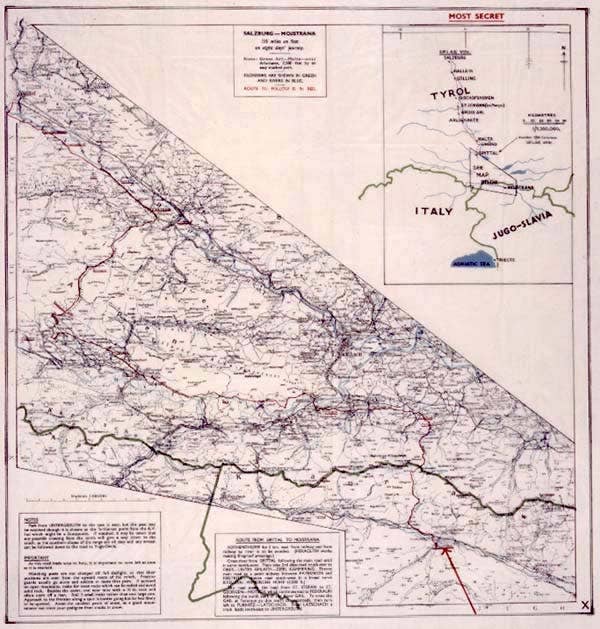

And these couldn’t be just any old maps, either.

An escapee who rustles is an escapee who’s just that little bit more likely to get killed.

“Victor and I became friendly.

“Our entire mindset was always based on: how can we beat these guys?

Waddingtons feels like De La Rue is the devil.”

The real devil was waiting in the wings, however.

All despite their rivalry.”

Waddingtons had leapt in to save the day and was now on MI9’s radar as a result.

Clayton Hutton was quick to act.

Once satisfied, Alston returned to read the firm the official secrets act and explain the escape maps plan.

In the years that followed, Waddingtons began turning out silk maps for Clayton Hutton and his various kits.

Waddingtons was also asked to lend a hand in related areas, too.

Clayton Hutton’s eventual solution capitalised on all of this beautifully.

In truth, though, MI9’s boldness is yet more proof of how unprecedented its mission was.

(Turing lost, incidentally.)

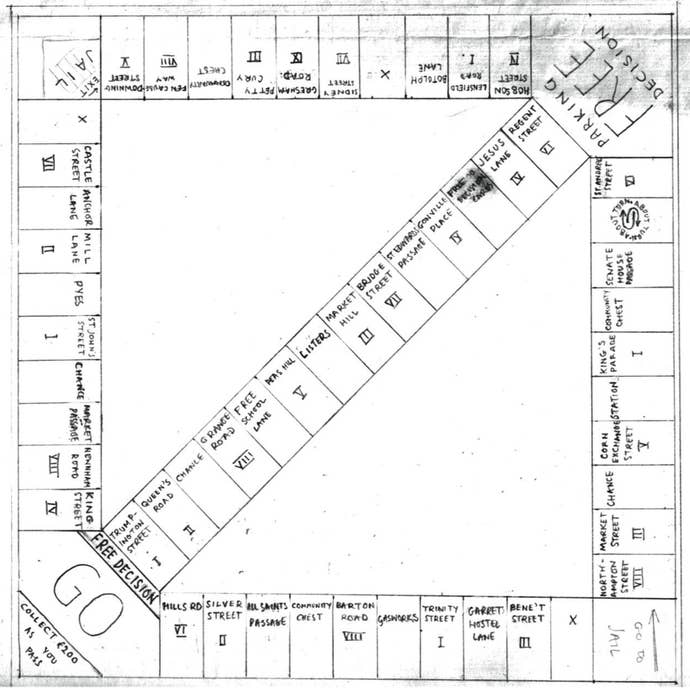

MI9 didn’t overlook board games, either - and one board game in particular.

Free parking

Somewhere around 1943, Monopoly entered the Second World War in style.

It had to be in style, really: there was no other workable choice.

This is why the fancier - and more expensive - Deluxe edition was probably employed.

“The box would have been the same size as the game board.

The board fit into the box, and the box was maybe an inch in depth.

That’s what would have been shipped into the German POW camps.”

And what would have been inside it?

“Many communications were by word of mouth and never written down for security reasons… Did the Monopoly gambit work?

If you’re winning, you often discover that there’s something peculiarly hollow about the achievement.

He was a schemer and a plotter by nature, and these sorts of people often require an antagonist.

His energy needed some kind of focus, and as Germany crumbled, that focus was weakening.

He was also highly-strung; he went on to have a nervous breakdown brought on by overwork.”

In this light, the last section of Official Secret is heartbreaking.

The best stuff’s all still classified - the deal is compromised.

It’s Houdini and the packing crate all over again.

This is one of the most interesting questions hanging over the whole affair, in fact.

“I’ve asked that question more than once to Victor,” says Orbanes.

What did they have?

You needed tools, you needed currency.

Bribing was fairly commonplace.

A potential life-improver at least.”

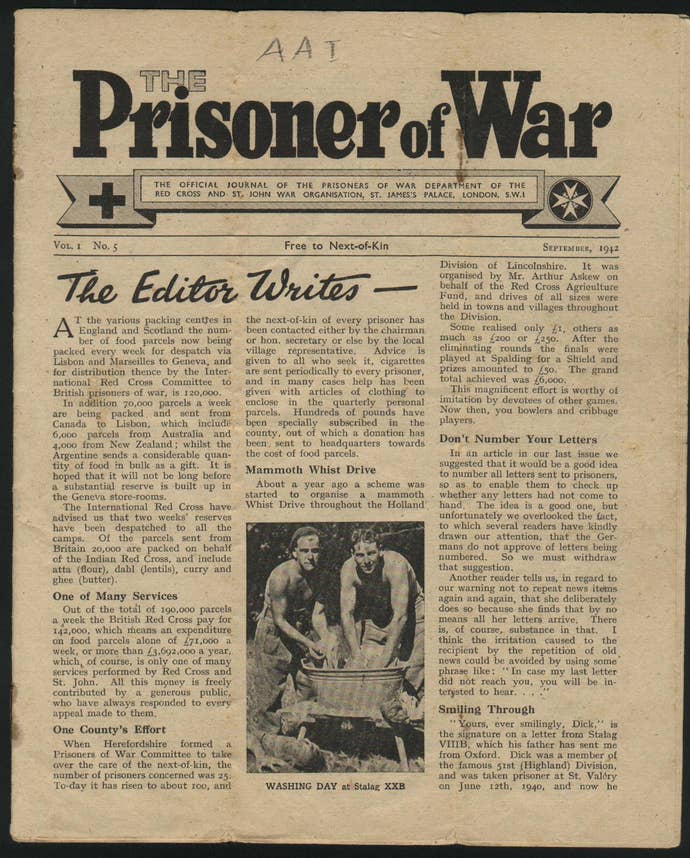

“It has been estimated that about half of these would have had a silk map with them.

But presumably any map is better than none.”

As for Monopoly, though?

That’s a different story.

“That’s true,” says Orbanes when I mention this.

“And it is such a shame.

In the Imperial War Museum, you’ve got the option to see the display of escape materials.

you could see silk maps, you could see playing cards.

But you will not see a Monopoly game.”

Some researchers have cast doubt on the heroic tale, though - and they have some interesting arguments.

“If these special edition wartime games exist, they will eventually surface.

Probably will be outside my range, but still will be rather exciting to see one.

If none shows up in the next five years, then I will question if any were ever made.

A large part of the answer regarding the missing boards may lie with the production numbers.

“No, they made each set custom.

It wouldn’t help to have an escape map for your grandfather for France, right?

He was in Poland.

That’s a very important point to make.

“There were not thousands of these things,” he continues.

“There may have been hundreds.

They were just free to tell their stories and they did it in such vivid detail.”

“The letters between Clayton Hutton and Waddington certainly imply that this was the intention.

The total amount of illegal material sent in this way must have been considerable.”

XXB

Whether the Monopoly escape kits ever made it out of Waddingtons probablyshouldn’tmatter.

Weaponised Snakes and Ladders!

That’s still a pretty good story, all told.

It’s Monopoly that makes it agreatstory, though.

It’s Monopoly that transforms this plucky narrative into something that’s truly memorable.

A potential life-improver at least.

Yet I often think of my grandfather in that prison in Poland, and I wonder about him.

Even today, I still don’t know many of the details of my grandfather’s wartime experience.

I do have one dark story he used to tell my mother, though.

So what could his life have been like out there?

His narrative has a kind of sustained and even-tempoed awfulness to it.

“A dog’s skin made excellent gloves or covers for your feet,” he explains.

“It was a primeval existence, back to the caveman.”

And yet Monopoly must havehelpedin its own quiet way, and in its own quiet moments?

They will provide you will the illusion, at least, of agency.

Maybe sometimes the illusion is enough.

There’s another potential reason why no sets were recovered after the war, and it’s fascinating.

‘And if you have any records whatsoever pertaining to this, destroy them as well.'”

“I find this to be wonderful.

And they kept it preserved until they knew it would no longer be applicable.”

That’s an idea that even Clayton Hutton would admire, I suspect.

The long con - four decades long - delivered with a tart thematic twist.

Langley and Churchill’s Wizards: The British Genius for Deception, by Nicholas Rankin.

Additional thanks to Paul Presley of the brilliantContinue Magazine.Any errors are mine, unfortunately.