I often think about how memory doesn’t exist.

Our past is, instead, a complex process of reconstruction.

How much does my brain mislead me about my own past?

Perhaps the answer is best found in something that was concretely defined in my childhood.

After more than twenty years, I want to talk about Myst.

I was two when Myst released in 1993.

By arriving so seldom, they became more formative.

Myst stayed with me not because it inspired a particular feeling in me, but because it inspired nothing.

I made no progress in the game.

I didn’t make it out of the first age.

I’m not sure I even solved a puzzle.

We enjoy some games and we don’t enjoy others.

It became one ofthosegames; one of those that sit in your backlog, brighter than others.

As someone who thrives on being told what to do (whowantsto make their own decisions?

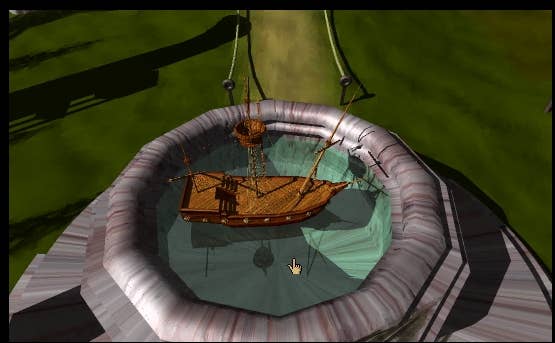

Myst is a surprisingly simple game beneath its complex challenges.

You are dumped on a small island dense with puzzles and all the requisite information needed to solve them.

These puzzles often require lateral thinking, at times a good ear for sound, and solid memory.

After years of dreading Myst, I was surprised to find myself moving smoothly through the game.

Shockingly, my problem-solving skills had, in fact, improved since I was nine.

This caused the friend monitoring my progress to have a minor conniption.

In my defence, it wasn’t all a fluke.

Solving a puzzle in Myst, it turns out, is a lot like writing.

Yet, like writing, few things feel quite as satisfying as the moment when the solution comes together.

I breezed through Myst (and its sequel, Riven) and had a blast doing it.

Maybe I actually like celery, maybe Icanswim, maybe I’ve been too harsh onHideo Kojima.

No, let’s not take this too far.

I come from a family with a strong history of dementia.

It’s scary, scarier than the memories of Myst that stopped me playing it.