“They are just sitting on this world of history and it’s on a Google Drive.”

Silent-era American films have a better survival rate than classic video games.

Let that sink in.

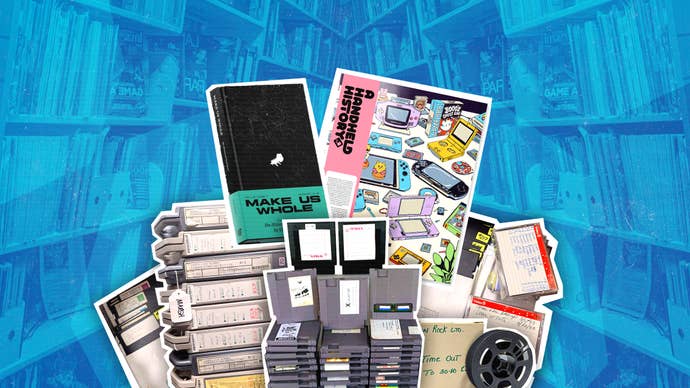

What this means materially is that only 13 percent of games released before 2010 are readily accessible today.

They live in our memories more than they do in physical media.

Salvador was instrumental in thelaunch of the Video Game History Foundation’s new digital library.

But that doesn’t mean that the Video Game History Foundation is giving up.

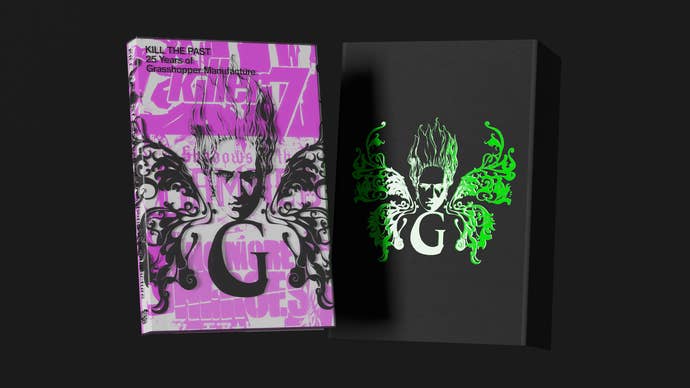

Lost in Cultrecently announceda 25-year retrospective documentary book chronicling the history of cult Japanese studio, Grasshopper Manufacture.

This book stands as material evidence of the collaboration between preservationists of culture and producers of commercial video games.

However, not every preservation project leads to the promised Google Drive full of unearthed treasures.

Accord’s Library has now closed following contact from Square Enix’s legal team.

Salvador hits on a perhaps underrepresented threat produced by the current precarity of the video games jobs market.

With game studios churning through staff members, in-house preservation advocates are going to become increasingly rare.

It’s something there hasn’t really been a lot of dedicated organisational support to doing."

Without that support, what are game history fans meant to do?

Well, if we turn to historical precedent, what they tend to do is steal.

The majority of preservation projects have been ad-hoc, community-led deep dives into specific niches requiring less-than-legal DRM workarounds.

A new approach is needed, then.

I feel that’s a bit useless.

Like, what are we learning from that?

Apart from being smug about the past?"

This general smugness is largely attributed to the demographic of folks working in the game history space.

A demographic that needs to develop if this preservation is to be taken seriously as a practice.

We need to understand what these games meant for people of all backgrounds.

So where does that leave us in 2025?

Salvador expressed it best in my conversation with him.

We were discussing the recent re-discovery of Piglet’s Big Game that went viral last year.

“If I could idealise what the future of game history looks like.

I want a thousand Piglet’s Big Game.

That is something that gives me hope.”