“Conceptually, it was very different to most games,” he explains to me via Skype.

“I already had the idea for the board game,” explains Toms.

“So I just thought a computer could do that, too.”

From a young age, Toms harboured dreams of having a career in tabletop games.

The inevitable reply came back.

“He said it was a phase and that I’d grow out of it.”

Undeterred, Toms continued with his main project, a combination of two of his loves.

“I’m a football fan.

I love football, although as a Torquay United fan, I’m used to suffering!”

But fusing the sport into board game form was proving tricky.

“I found it frustrating because certain things were very clunky.

Then, in the early 80s, he spotted a TRS-80 clone while strolling in Tottenham Court Road.

“But it still cost 325 [around 1600 today].

The switch from table to CPU was inspired.

Despite the lack of graphics, he knew he was onto something when his friends played the result.

“When people played it, they wouldn’t get off it.

It had an addictive quality.”

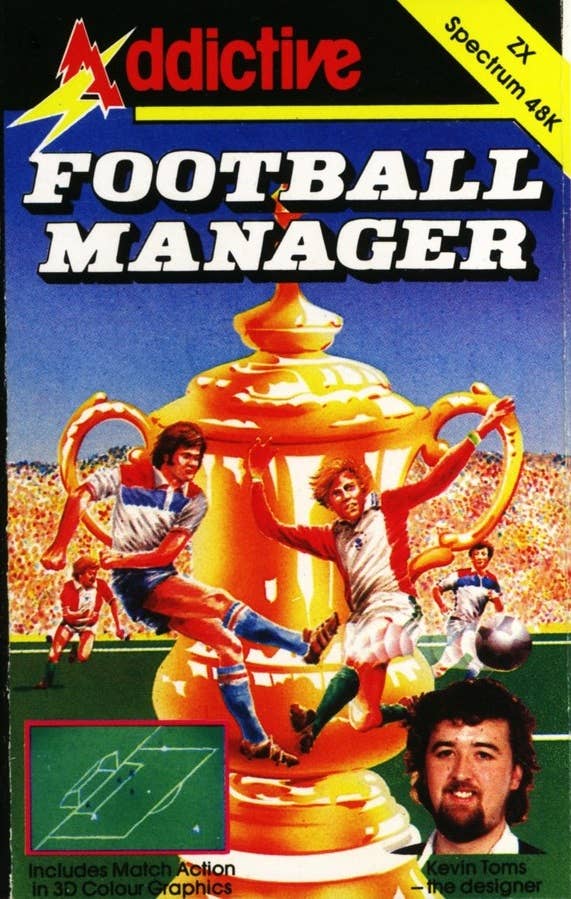

Sensing a real commercial opportunity, Toms used his initial impression to good effect.

“I thought it was a good name, and accurate, because Football Manager was very addictive.”

Addictive Games was born, and then, in 1981, Sinclair Research unveiled its game-changing micro.

“I had looked at the ZX80, but it was only 1K,” says Toms.

The format breakdown was 297 on the ZX81 and just three on the Video Genie.

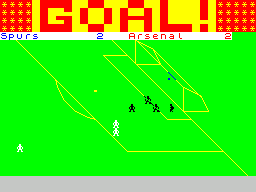

Under the hood, the key to Football Manager is its maths and match engine, as Toms explains.

“It uses the attributes of the teams but with a random element.

It’s a combination of algorithms and tuning, so in the end, the results are realistic.

If a top team plays a bottom team, they’ll normally win.

But it doesn’t always go to plan.”

In a unique respect, Toms was recreating the glorious uncertainty of football.

“Over the years, Southampton fans have given me so much grief!”

The original versions of Football Manager failed to include the south coast club.

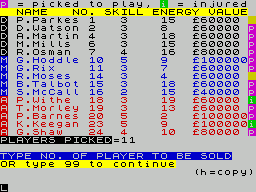

As was common at the time, memory dictated everything.

“The amount of text in the names of players and teams was critical.

Everything in the original design was brutally pared down to work in the small memory.

The transfer market is very lean and mean, but it works very well.”

It was another memory-based decision by Toms.

“It was the most efficient way I could keep the game’s challenge going.

As with the ZX81, Sinclair transformed the market again in 1982 with its follow-up, the ZX Spectrum.

Toms, still part-time, acknowledges this was another turning point.

he grins when I mention this.

“I had to do a new cover for Smith’s.

And I saw a connection between computer games and books and music.

Who cares that EMI is publishing a band?

All people care about is the band.”

The result was the Kevin Toms fizzog proudly displayed on every copy of Football Manager.

“I thought, this is good enough, I’ll put my face on it.

Then it just took off and became this thing.

I never understood why others didn’t do it.”

“But that’s not true - the game works it out as it happens.

If you repeated certain moves, people would very quickly recognise that.”

As Addictive Games became Toms' full-time focus, more games appeared, such as Software Star and President.

Copycats were rife, and by the time Addictive released Football Manager 2, the competition was fierce.

Nevertheless, it was still a decent seller, no doubt helped by the legendary status of its forebear.

I don’t like lots and lots of stats.

I prefer a more subtle depth.”

It’s that core simplicity of Football Manager that ensures it still appeals to so many today.

“The connection for me was that I created something entertaining,” concludes Toms.