“We wanted it to be different.”

Hence the development detox for Warriner and Cummins, despatched to a remote Cecil family cottage in North Wales.

When the pair returned, they had a 12-page design for Revolution’s next game.

So, how did the creative process work?

“I don’t know,” laughs Warriner.

“But it was like, what is the game going to be?”

When security officers arrive from Union City and cause havoc, Foster is taken back to the city.

“And, to his credit, he said, ‘Get rid of all that shit.

Just have the left and right clicks’.

And we were like, ‘You’re right!'”

“By offering just two actions - interact and look - we reduced the number of permutations enormously.

But then we attracted criticism about the game being too easy.

That’s sort of the price you have to pay.”

Cecil nods in agreement.

We wanted it to be different."

It was a shame because it could have been a good licence."

We shipped him an Amiga because he was so excited to start designing characters in DPaint."

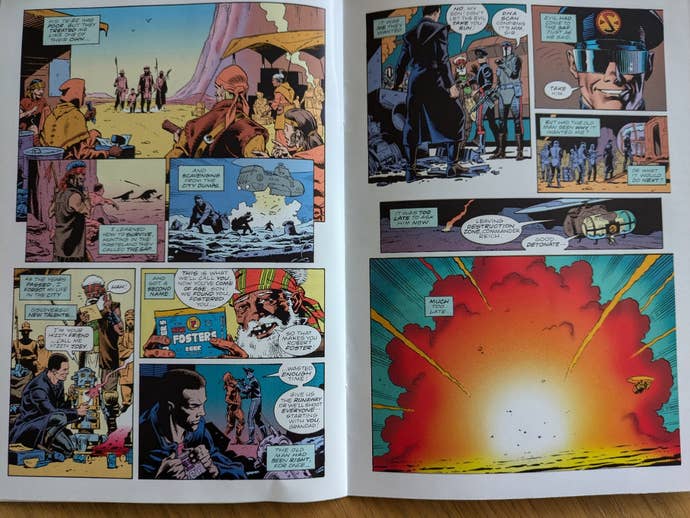

Ultimately, Gibbons would also design many of Steel Sky’s emotive backdrops and the game’s overall design.

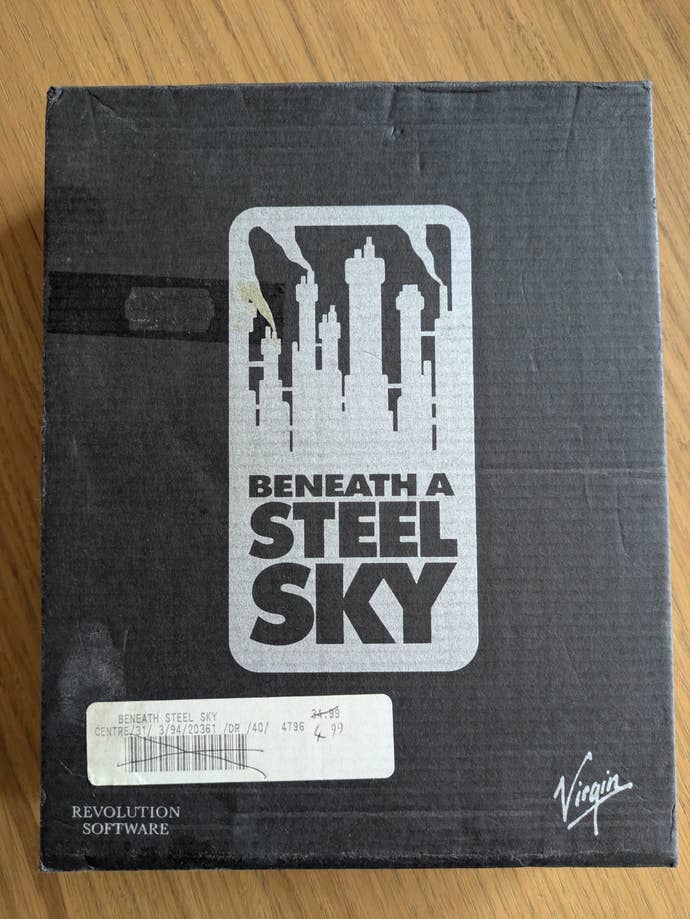

Plus, of course, the comic bundled within the game’s large black box.

“By today’s standards, it was not a big piece of programming,” says Warriner.

“And no money.

But there was a lot of creative stuff going on.”

“Steel Sky was just hacked out,” smiles Cecil.

It ended up being so much more than the sum of its parts.

It’s a game with soul."

“Virgin were very supportive, and yes, we did keep running out of money.

But it found creative ways to fund it a little more.”

“We kind of struggled through this, and it was absolutely dire,” laughs Cecil.

“And in the end, we were saved by Konami.

The situation allowed Revolution to jettison what it had already recorded and start again from scratch.

“People seemed to forgive weaknesses if you did that, because things were changing so fast.

“[Beneath a Steel Sky] was a pivotal game for Revolution,” muses Cecil.

Because it was difficult.

And it was highly pressured.

But creatively, it was terrific.”